Waranowitz! He Speaks!

Or at least he’s written an affidavit that’s kind of a stunner.

Stay with me here. There’s been a development in Adnan’s case — to me, the most interesting one I’ve seen. And it comes from, of all people, the cell phone expert who testified at Adnan’s trial. Abraham Waranowitz.

Waranowitz was the radio frequency engineer for AT&T who testified at Adnan’s trial about what cell towers pinged at what locations on the day that Hae Min Lee went missing in 1999. His job on the stand was to decode cell phone data that AT&T had handed over to the detectives.

And while Waranowitz’s words on the stand were few, and technical, and soporific [see Episode 5, where I admitted to being so bored by the whole thing that I handed it all over to our producer Dana Chivvis to investigate], his testimony was in fact fantastically important. That’s because the cell records from Adnan’s phone that day were used to corroborate Jay’s story about what happened. So Waranowitz’s interpretation of those cell records underpinned the state’s entire case against Adnan.

I can’t stress this enough: If you can’t link the cell records to Jay’s story, the case against Adnan is much harder to prove. Remember the incoming 7:09 p.m. and 7:16 p.m. calls that the prosecution claimed put Adnan and Jay together in Leakin Park, where Hae’s body was buried? Waranowitz’s testimony is how they’re able to place them in that park, at that time. Those two calls were huge for the state’s case — the prosecutors touted them repeatedly, in opening statements, in closing statements, because they seemed so incontrovertible.

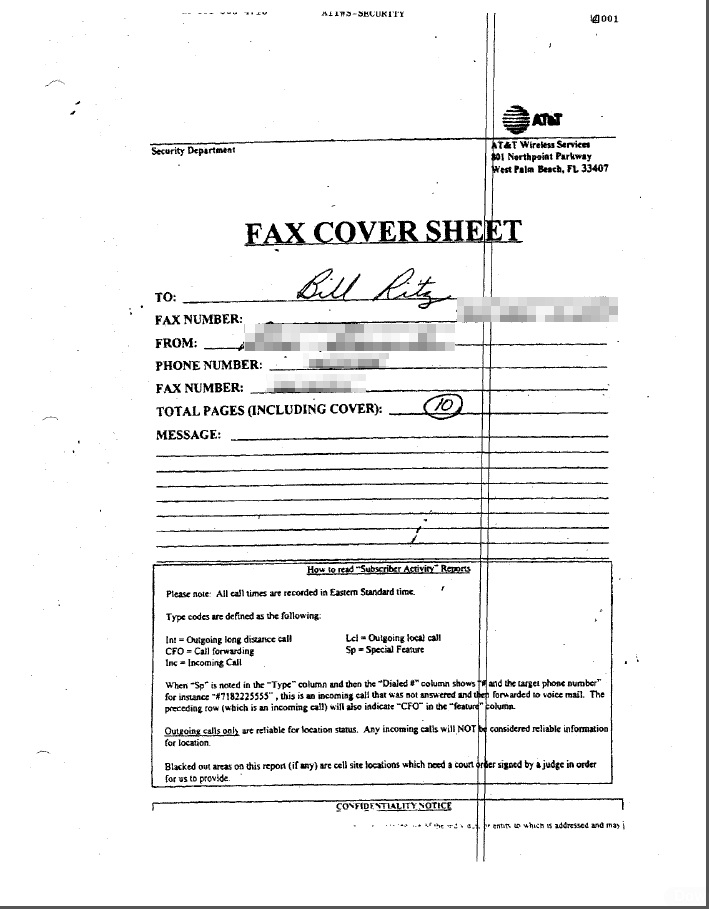

Now comes Waranowitz to say he doesn’t stand behind his testimony. I know! That’s why I’m stunned. In an affidavit he wrote for the defense, Waranowitz says he never saw a “critical” disclaimer that AT&T had attached to the call records, explaining the following: “Outgoing calls only are reliable for location status. Any incoming calls will NOT be considered reliable information for location.” That disclaimer was on the fax cover page that AT&T included in all its communications with the Baltimore homicide detectives in this case. But Waranowitz says he never saw it.

The AT&T fax cover sheet.

In an affidavit dated just ten days ago, on October 5, 2015, he writes: “Just prior to my testimony, in the courthouse, [Prosecutor Kevin] Urick presented me with a document — which I was viewing for the first time — referred to as State’s Exhibit 31. I remember viewing one page of the document. Since this appeared to have ordinary AT&T cell site data on it, I accepted it as it was presented.” He goes on to explain: “What Urick did not tell me, or call my attention to, in relation to Exhibit 31, was that AT&T had previously issued the disclaimer…” about the incoming calls not being reliable for location. Waranowitz says he wasn’t familiar with records like the one he was holding in that moment — he was used to working with raw data from the switch. Waranowitz called the disclaimer “critical information for me to address. I do not know why this information was not pointed out to me.”

“If I had been made aware of this disclaimer, it would have affected my testimony,” he wrote. “I would not have affirmed the interpretation of a phone’s possible geographical location until I could ascertain the reasons and details for the disclaimer.”

In other words, until he had sussed out what the disclaimer meant, he wouldn’t have been able to answer some of the questions Prosecutor Kevin Urick put to him on the stand, such as: Does Jay’s story about being in Leakin Park with Adnan at around 7 pm that night line up with the cell science? Waranowitz is now saying he can’t be sure about it. That his own testimony is potentially unreliable.

I’m stopping myself right now from using another exclamation point. Because while I find this an incredibly surprising development, it’s also, to me, inconclusive. In terms of Adnan’s case in court, it sure sounds like a pretty big deal if an important witness says he can’t vouch for his testimony. But I do not know whether the Circuit Court will even take up this disclaimer issue. It doesn’t have to. And in terms of understanding what happened to Hae Min Lee, it doesn’t mean anything - at least not yet, not until we know exactly what the disclaimer about incoming calls means.

Last year, when we were reporting the Adnan Syed case, we here at Serial actually spent a good chunk of time investigating this very same disclaimer on the fax cover page from AT&T. Dana emailed and called AT&T repeatedly, but they never answered the question about the disclaimer. Dana also wrote to Waranowitz, asking for help understanding the cell records, but he never responded. Finally Dana ran the disclaimer past a couple of cell phone experts, the same guys who had reviewed, at our request, all the cell phone testimony from Adnan’s trial, and they said, as far as the science goes, it shouldn’t matter: incoming or outgoing, it shouldn’t change which tower your phone uses. Maybe it was an idiosyncrasy to do with AT&T’s record-keeping, the experts said, but again, for location data, it shouldn’t make a difference whether the call was going out or coming in.

So we figured maybe everybody involved in the trial understood the incoming-outgoing science to work the same way — that is, Waranowitz, Adnan’s attorney, the prosecution — and that the cell science presented at trial was sound, and so maybe the disclaimer wasn’t a big deal and maybe that’s why no one ever brought it up at trial. So we let it go. Which was a mistake, apparently. Because now we find out that Waranowitz, the only guy who absolutely should have known about it, did not, and that he’s just as confused as we were (and still are).

Dana went back to AT&T yesterday, to ask them, once again, to explain the disclaimer. And this time, an answer! Supremely unsatisfying, but an answer: “Since this involves an ongoing court case we don’t have anything to add beyond what’s in testimony and filings.”

And I emailed Waranowitz again yesterday, about what his understanding of the disclaimer is and whether he’s going to try to find out what it means from AT&T (he no longer works there). But no word back so far. I’m not optimistic. I found this on his LinkedIn page, regarding his testimony in Adnan’s case:

I presented an honest, factual characterization of the ATTWS cellular network, and had no bias for or against the accused. How that evidence was used (or debatably misused, or ignored) was not disclosed to me. …

Waranowitz made it clear in the note that he’ll be keeping his opinions of the trial to himself, and that he’s not saying anything else about it publicly. “Please do NOT contact me,” he wrote.

Waranowitz’s affidavit is the latest in an ongoing legal conversation between Adnan’s appellate attorney, C. Justin Brown, and Deputy Attorney General Thiru Vignarajah. Actually, “conversation” makes it sound both more boring and less dripping with mutual disdain than it actually is. It’s good reading: You can check out the latest filings here.

It all started after Maryland’s Court of Special Appeals sent the Asia McClain alibi question back to the Circuit Court (see our May 27 newsletter). At the very end of June, Justin Brown started that Circuit Court process rolling: He filed a motion to re-open Adnan’s post-conviction case. Two months later, in August, Brown filed a supplement to that motion, adding the “unambiguous warning” on the AT&T fax cover page as another thing he wanted the court to consider: “The evidence Syed now presents to the Court … shows that the cell tower evidence was misleading and it should have never been admitted at trial.” It was another example of ineffective assistance of counsel, Brown argued, since Adnan’s trial attorney, M. Cristina Gutierrez, had seen the fax cover page in question but had failed to make a thing of it at trial.

In September, the state responded in the form of a 34-page filing so wonderfully crafted, so supercilious, that it makes me imagine a frowning barrister in a white curly wig and half-moon glasses. First off, Vignarajah argues, the whole endeavor is meritless — the circuit court shouldn’t entertain any of Adnan’s claims that he had ineffective assistance of counsel:

To be sure, enshrined in the Constitution is a guarantee that every criminal defendant will have effective representation. ... But that safeguard is not an invitation to second guess tactical decisions and trial strategy, nor does it give license to smear the reputation of defense attorneys from the comfortable perch of history and of hindsight. The promise of the Sixth Amendment is sacrosanct, and there are no doubt defendants who are deprived of it. Adnan Syed, however, is no such victim.

The claims Adnan brings up in the filing are misleading, unauthorized and untimely, Vignarajah writes, but the state will stoop to answer them, nonetheless. Those fax cover sheets, he explains, were included with every fax that AT&T sent to the detectives in this case [as far as I can tell, that’s true - I’ve seen four of them in the case files, corresponding to four different sets of documents]. In this next part, it’s almost like Vignarajah is biting his tongue, not wanting to call Justin Brown a sad little man:

The State is compelled, however, to also point out that even a cursory review of the cell tower records and fax cover sheets makes it clear that what Syed characterizes as an “unambiguous warning” does not relate to the cell tower records relied upon at trial by the State’s expert and admitted into evidence, but rather applies to information listed on documents titled “Subscriber Activity” reports.

The defense simply doesn’t understand what the exhibit in question — Exhibit 31 — is all about, explains Vignarajah.

The flaw in Syed’s argument is that the cellphone records relied upon by the State’s expert and entered into evidence at trial were not Subscriber Activity reports. … Under these circumstances — and having corrected the misimpression advanced, presumably inadvertently, by Syed — counsel’s failure to confront the State’s expert witness with a fax cover sheet that corresponded to an altogether different document can hardly be called ineffective … Indeed, had Gutierrez challenged the State’s expert with a notation in a boilerplate legend from a generic fax cover sheet that applied to a separate report, she would have run the unwarranted risk of looking foolish or disingenuous to the jury.

Exhibit 31 consisted of five pages, three of which were cell records from Adnan’s phone, showing incoming and outgoing calls, and cell tower locations. The AG is saying that that specific disclaimer — which, again, was included in boilerplate language on all fax cover pages from AT&T regarding Adnan’s case, only refers to “subscriber activity reports,” and Exhibit 31 isn’t a subscriber activity report, and therefore the disclaimer doesn’t apply.

There, there, Justin Brown. Don’t feel bad. We all make mistakes.

And then, two days ago, Justin Brown filed his reply to the State, complete with Waranowitz bombshell. That filing rather neatly points out that, um, the State is wrong. Exhibit 31 is a subscriber activity report. And I agree with Brown about that, largely because on the very first page of the original 24-page call log (three pages of which would later become Exhibit 31 at trial) two words appear at the top: “Subscriber Activity.” So. It’s clear. There was a disclaimer on the fax cover page of that report; that report consisted of “subscriber activity;” and that subscriber activity is the substance of Exhibit 31.

Brown all but thanks Vignarajah in his most recent filing. Because if Vignarajah hadn’t mentioned that bit about all AT&T faxes to the detectives having that same cover page, regardless of their content, Brown wouldn’t have understood that the state must have known that this Exhibit 31 report had the same disclaimer. So now Brown adds another claim he’d like the Circuit Court to consider: a Brady violation. The state, he argues, knowingly withheld exculpatory evidence at trial, because it entered Exhibit 31 into evidence, purposely omitting both the fax cover page that included the disclaimer about how to interpret incoming calls on subscriber activity, and the page of the report that identified it as a subscriber activity report.

So that’s where it stands today. Once again, I want to be clear: It’s possible the disclaimer wouldn’t have been relevant to the cell science. After all, maybe it was just a cover-your-ass disclaimer in the unlikely event of a billing or software glitch on the part of AT&T. And hence it’s also possible that Waranowitz’s testimony would have been unchanged even if he had seen and understood the disclaimer. We just don’t know.

Meanwhile, the back and forth of this post-conviction fight is not over. From my old friend David Nitkin (formerly a Baltimore Sun colleague, now a spokesman at the AG’s office): "The Office of the Attorney General is reviewing Mr. Syed's latest filing and a decision on whether and how to reply is pending."

And when is Season 2 coming? We know, we know! We’re reporting it just as fast as we can. We’ll announce a date soon…